|

| Home | Bio | Art | Music | Literature | Civilization & Culture | Philosophy of Wholeness | Theosophy & Spirituality | Astrology |

THE ASTROLOGY

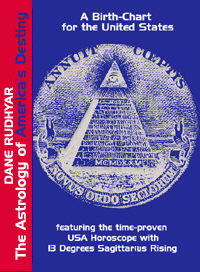

OF AMERICA'S DESTINY A Birth-Chart for the USA by Dane Rudhyar, 1974 THE ASTROLOGY OF AMERICA'S DESTINY Table of Contents

1. The Birth of the United States

as a Collective Person 2. The Roots of the American Nation 3. America's Place in the Cosmic Process 4. A Birth Chart for the United States of America 5. Two Hundred Years of Growth Through Crisis 6. A Chart for the Beginning of the Federal Government Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 7. America at the Crossroads 8. Prospects for the Last Quarter Century Illustrations • George Washington receiving the horoscope of America from the Angel Gabriel • The Reverse Side of the Great Seal of the United States • A Chart for the United States of America • A Chart for the Beginning of the Federal Government • A Chart for Richard M. Nixon • A Chart for the Twentieth Century |

CHAPTER SIX:

A Chart for the Beginning of the Federal Government - 3 The men who framed the Constitution in Philadelphia were all "distinguished" men selected by their own states (Rhode Island was the only state not represented). They are described by James M. Beek (The Constitution of the United States) as "men of substance and honor, who would debate for four months during the depressing weather of a hot summer without losing their tempers except momentarily — and this despite vital differences — and who showed that genius of toleration and reconciliation of conflicting views, inspired by a common fidelity to a great objective, that is the highest work of statesmanship." While this is no doubt true, I should add that the vast majority of these men were lawyers (thirty-nine out of the fifty-five delegates who attended the sessions), merchants, bankers, politicians — professional men and members of the wealthier classes. As Charles A. Beard points out, as a class or group, they had economic interest in producing a document that would provide a kind of insurance against the possibility that "we, the people" might insist on a too direct and participatory type of democracy. Actually the Constitution's original purpose was to do away with the ineffectiveness of the existing confederation of states; this meant above all to establish a strong Executive able to enforce decisions of the Congress. The main topics of discussion were matters referring to the degree to which the states would surrender some of their rights to a central authority, and therefore to the character and power of the federal government and particularly of its legislative body. What is called "the Great Compromise" led to the creation of two legislative bodies, the House of Representatives and the Senate, with different lengths of tenure of office. One of the strangest compromises between ideals of human freedom and the economic reality of slavery resulted in three-fifths of all slaves being counted as parts of a state's population in determining the number of its representatives in the House of Representatives — the slaves and other classes of persons having, nevertheless, no voting rights. As the historian Max Farrow has stated: There would seem to be only one way to explain and only one way to understand the "bundle of compromises" known as the Constitution of the United States. John Quincy Adams describes it when he said that "it had been extorted from the grinding necessity of a reluctant nation." The Constitution was a practical piece of work for very practical purposes. It was designed to meet certain specific needs. It was the result of an attempt to remedy the defects experienced in the government under the Articles of Confederation.(6)What the Constitution did not attempt to do was to define in concrete and functional terms precisely what the Preamble meant by "general welfare" and "the blessings of liberty." It is easy to speak of "justice" and "domestic tranquillity," but these terms, like the today's much-talked-about "law and order," would raise the basic issue of the validity of the status quo which the traditional structure of European society, rather than European governments, had bequeathed to the people of the New World. How could it be really a "new" world if a social revolution, more basic than that which did away with hereditary aristocracy and titles, was not to be recognized and clearly accepted as the purpose or destiny of the nation as a whole? Jefferson and a very few others apparently realized this, and more than any other participants in the liberation of the American people from England, Thomas Paine understood it when he asked not only for a breaking away from the political past of Europe, but from the cultural and religious prejudices of European society. This totally new beginning was announced on the reverse side of the Great Seal. But the "New Order of the Centuries" demanded far more of the Founding Fathers than their class-structured mentality could envision, far more than even the Bill of Rights — which came as an afterthought — would promise. Yet some kind of concrete and practical start had to be made. The new national entity had to gain the power to survive, politically and economically, within the tempestuous international environment of the Western world — just as a child has to build an ego to survive through the crises of his often inharmonious family world and the wars or revolutions of his larger social environment. The United States Constitution became the prototype of many similar ego-patterns for newly formed national entities. If it did not solve all problems, it was not only because the founders of the United States were simple men concerned with the practical problems of the day as they understood them, but also because world conditions altered at a fantastic and disconcerting pace after its promulgation; neither does the ego of a young person succeed in preventing the rise of psychological problems when he reaches the age of maturity. The Saturnian power of the ego has to be challenged, to be made flexible and open to wider realizations of human values. The great dreams of the teen-ager nearing the coming-of-age period have to be reinterpreted, reoriented, and if possible made effectual realities later on. 6. Cf. The Historians' History of the United States, 2 vols., edited by Andrew S. Berkey and James P. Shenton (Capricorn Books, New York, 1972). Vol. 1, P. 327. Return By permission of Leyla Rudhyar Hill Copyright © 1974 by Dane Rudhyar and Copyright © 2001 by Leyla Rudhyar Hill All Rights Reserved.  Web design and all data, text and graphics appearing on this site are protected by US and International Copyright and are not to be reproduced, distributed, circulated, offered for sale, or given away, in any form, by any means, electronic or conventional. See Notices for full copyright statement and conditions of use. Web design copyright © 2000-2004 by Michael R. Meyer. All Rights Reserved. |

|