|

| Home | Bio | Art | Music | Literature | Civilization & Culture | Philosophy of Wholeness | Theosophy & Spirituality | Astrology |

THE ASTROLOGY

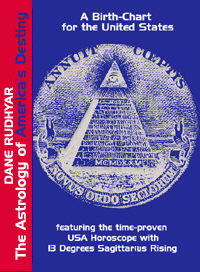

OF AMERICA'S DESTINY A Birth-Chart for the USA by Dane Rudhyar, 1974 THE ASTROLOGY OF AMERICA'S DESTINY Table of Contents

1. The Birth of the United States

as a Collective Person 2.The Roots of the American Nation Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 3. America's Place in the Cosmic Process 4. A Birth Chart for the United States of America 5. Two Hundred Years of Growth Through Crisis 6. A Chart for the Beginning of the Federal Government 7. America at the Crossroads 8. Prospects for the Last Quarter Century Illustrations • George Washington receiving the horoscope of America from the Angel Gabriel • The Reverse Side of the Great Seal of the United States • A Chart for the United States of America • A Chart for the Beginning of the Federal Government • A Chart for Richard M. Nixon • A Chart for the Twentieth Century |

CHAPTER TWO:

The Roots of the American Nation - 6 These words — "We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness" reclaimed the beliefs of a relatively small group — of educated men who had been stirred by the ideals formulated by the Humanists and the intellectuals of the Renaissance and the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Among these men, Francis Bacon occupies an out standing place for his books had a tremendous importance in the development of the modem scientific mentality. He has been called "the founding father of modem science," to which he gave "its method and its inspiration."(3) The publication of his Novum Organum in 1620 is a significant date in the evolution of the Western mind. He himself stated that he "rang the bell which brought the wits together." He set himself against both the medieval Schoolmen and their empty theological and metaphysical discourses, and the new Renaissance cult of rediscovered "classics" of the Greco-Latin civilization. He insisted on the need to separate science — as an experimental, analytical and inductive method of objective and rationalistic knowledge — from metaphysics, the search, of "final causes." He envisioned a vast, organized and critical accumulation of data based on judicious experiments into the "regularities of nature." He spoke of his scientific method as the Great Instauration, considering himself a pioneer eager to break with the past; because he believed in absolute (but not "divinely appointed") monarchy, be sought to obtain the king's financial support in building a college of science. In this, however, he failed, and he even lost his high office when he was accused of, and admitted to accepting, a form of political bribe, which, he claimed, did not affect his judgment — quite an up-to-date story which may not tell the whole truth. At any rate, his disgrace proved valuable, because as a result he found the time and incentive to write his major books. Bacon was soon followed by Newton and Descartes, whose ideas and works also became foundation stones on which so much of the edifice of modern science was built. President Woodrow Wilson, in his book The New Freedom, said that our Constitution was "written under the influence of the Newton theory of checks and balances." Still more important in the development of the collective mind of progressive intellectuals in Europe and in America was the Work of John Locke, the English empiricist. Locke (1632-1704) considered philosophy inferior to science and stated that as a philosopher he was "an under-labourer to the incomparable Mr. Newton." From the Newtonian and Cartesian view of the world he took his fundamental reliance upon "natural law." In his Two Treatises on Government (1699) he wrote that government originates in a contract and that it must obey certain natural, reasonable laws which set limits to its authority. While his ideas were mainly intended to give a solid and logical justification for the constitutional monarchy of England after the 1688 revolution, they provided the Progressives and malcontents in the American Colonies with a sort of textbook for a future revolution. Locke's works were introduced to France by Voltaire, and they greatly influenced the French philosophers and social reformers of the "Enlightenment." Before Jean Jacques Rousseau wrote his Social Contract, Locke declared that there was a state of nature in which men enjoyed complete liberty; that they had created by means of compact an authority superior to their individual wills; that the government thus established was endowed only with certain specific powers — above all, with the protection of property. These ideas are embodied in the first part of the Declaration of Independence after having passed through the mind of Jefferson, who was undoubtedly also greatly influenced by another Englishman who had reached America in 1773, Thomas Paine. As we have already seen, Paine's booklet Common Sense was a most, important factor in making the break between England and America more definite, especially in destroying the emotional loyalty of the colonists to the king and the English Constitution. Paine declared in the most violent terms the unworthiness of the English king. He stated that the union between England and America was "repugnant to reason, to the universal order of things, to all examples from former Ages." It was Nature herself that had declared the separation, he said, and he urged Americans to accept their destiny by thundering across the Atlantic a declaration of independence that would shake the throne itself, for indeed it was America's destiny, at all levels, to be a New World totally repudiating the iniquities and horrors of the human past. 3. Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Macmillan, 1967. Return By permission of Leyla Rudhyar Hill Copyright © 1974 by Dane Rudhyar and Copyright © 2001 by Leyla Rudhyar Hill All Rights Reserved.  Web design and all data, text and graphics appearing on this site are protected by US and International Copyright and are not to be reproduced, distributed, circulated, offered for sale, or given away, in any form, by any means, electronic or conventional. See Notices for full copyright statement and conditions of use. Web design copyright © 2000-2004 by Michael R. Meyer. All Rights Reserved. |

|